Doing History Through Art: The story of the green glasses

By Kamala Vasuki and Ponni Arasu

*This is the second offering by Ponni Arasu and Kamala Vasuki in the Doing History Through Art cluster of the multi-part series Holding Movements, Agitating Epistemes: Remembering, Retelling, and Dreaming for Justice convened and co-edited by Richa Nagar and Ponni Arasu.*

Vasuki and I are living through the worst economic crisis that Sri Lanka has witnessed since the 1930s. We are witnessing the non-stop violence of the state in myriad forms. We do not have access to essentials such as petrol, kerosene, cooking gas, etc. Petrol prices have quadrupled since the beginning of this year. the price of rice has doubled. Every part of the country is dotted with long queues for petrol, diesel, kerosene, and cooking gas now and everyone knows that similar queues will soon be seen for food items. There is exhaustion and apathy all around us. For the past twenty days the two of us have been a part of a daily satyagraha where anything from ten to forty people walk from the Mary statue outside St.Sebastian Church to the Gandhi statue in the public park in Batticaloa. We walk in silence and in one single line with children and adults of the many communities we work with. As we walk, we express our anguish, grief, protest, hopes, dreams, and questions. We create our own praxis of protest–the only thing perhaps that anchors us in an otherwise turbulent and scary time. As a part of this praxis–of remembering, hoping, and creating amid turbulence–we share with you a sliver of past journeys: already walked paths that have brought us to where we are in this moment we live.

The story of the green glasses

மக்கரம் (Macrame) என்ற விசயத்தை முதலில கேள்விப்பட்டது 1981-82 இல எண்டு நினைக்கிறன். இது தடித்த வெள்ளை நூலில் பின்னி செய்யப்படும் சுவர் அலங்காரங்களையும் அலங்கார உறிகளையும் குறிப்பது.

I heard of ‘Macrame’ first in 1981-82. This is a craft that involves plaiting thick white rope to make decorative objects for houses.

நாங்கள் அப்ப றக்கா ரோட்டில இருக்கிற ஒரு வீட்டில அனெக்ஸில இருந்தம். எல்லாரும் பெரியம்மா எண்டு கூப்பிடுற, மங்கையற்கரசி வித்தியாலய அதிபராக இருந்து ஓய்வு பெற்ற திருமதி கனகசபையினுடையது அந்த வீடு. அவவுடன் நாங்கள்; எல்லாரும் கனகராஜா மாமா எண்டு கூப்பிடுகிற பட்மின்டன் பயிற்றுனரான அவவுடைய மகனும் இருந்தார்.

At that time, we lived in the Rakka Road house, in the Annex. The house belonged to the retired principal of Mangaiyarkarasi Vidyalayam, Mrs. Kanagasabai. Everyone called her periyamma (aunt, mother’s older sister or father’s older brother’s wife). Her son lived with her. He was a Badminton coach. We all called him Kanagaraja Mama (uncle, mother’s younger brother or father’s sister’s husband).

அப்ப அம்மாவுக்கு கிட்டத்தட்ட 50 வயது – அவ மாமாவை அண்ணா எண்டு கூப்பிட்டபடியால கனகராஜா மாமாவுக்கு 50 வயதுக்கு மேலதான் இருந்திருக்கும். உயரமான கண்ணாடி போட்ட கம்பீரமான ஆள். சின்னப்பிள்ளைகளுடன் நேரம் செலவளிப்பதெண்டால் சரியான விருப்பம். என்னையும் தம்பியையும் சேர்த்து அந்த வீட்டை சுற்றியிருந்த வீடுகளில் ஏழெட்டுப் பிள்ளைகள் இருந்தோம். அனேகமாக பெண்பிள்ளைகள். லுஆஊயுயில இருந்த பட்மின்ரன் கோட்டுக்கு போகும் போது எங்களில் ஒரிருவரை சைக்கிளிளில் ஏற்றிக் கொண்டு போவார். மற்றவை அவருக்கு பின்னால் எங்கட சைக்கிளில போவோம். கதை தெரிஞ்சவை அவரை ஒரு பைட் பைப்பராகக் கற்பனை செய்து கொள்ளலாம்.

My mother must have been fifty years old at that time. She called mama, Anna – older brother. So he must have been more than fifty years old. He was a tall, majestic man and he wore glasses. He loved spending time with children. Including my brother and I, there were seven or eight children in that neighbourhood. We were mostly girls. When he went to the YMCA Badminton court, he would take a couple of us on his bicycle, with the rest of us following on our own bikes. For those who know the story, you can imagine him like a Pied Piper of sorts.

வீட்டை சுற்றியிருந்த பிள்ளைகளுக்கு பழக்குவதற்கென்றே வீட்டின்; முன் முற்றத்திலும் பின் முற்றத்திலும் பட்மின்டன் கோட் போட்டிருந்தார். (பட்மின்டன் கோட்டுக்கு கூகிளில் தமிழ் மொழிபெயர்ப்பு தேடினால் ‘பு+ப்பந்து நீதிமன்றம’; எண்டு வருகுது!!!!!).

He had made a badminton court in front of his house just so he could teach the game to the children in the neighbourhood.

மாமா சிறுபிள்ளைகளின் கற்பனைகளை விரிப்பதில் அலாதியான திறமை வாய்த்தவர். எங்களுக்கெண்டே கதைகள் சேர்த்துக் கொண்டு வருவார். வீட்டின் முன்பகுதிக்கு மட்டும் கொங்கிறீட் கூரை போடப்பட்டிருந்தது. அதற்கு மேல் ஏற்றி வானத்தைப் பார்க்க வைப்பார். ஒரு மேசைக்கு மேல கதிரை வைச்சு அதில ஏறி கொங்கிறீட்டில தொங்க வேணும் – கையால அதில் தொங்கிக் கொண்டு ஒரு கால வீசித் தூக்கி மேல கொண்டு போய் அந்தக் கொங்கிறீட் தட்டுக்கு கிட்ட இருக்கிற கிறில் கல்லில வைக்க வேணும். இப்ப மற்றக் காலை கொங்கிறீட் தட்டுக்கு மேல வைச்சு ஒரு எட்டு எட்டி மேலை போய் விடலாம்.

Mama was very skilled in expanding our imaginations. He would collect stories just so that he could recite them to us. There was a concrete roof in the front half of his house. He would make us climb that roof and look at the sky. We would put a chair above a table and then hang from the concrete. As we hung with our hands, we had to lift one leg up to the concrete and balance that leg on to a stone grill on the side. We then lifted up the other leg onto the concrete and pushed ourselves up to get on to the roof.

கூரைக்கு மேல இருந்து பறக்கும் பு+ச்சிகளிலும் பறவைகளிலும் தொடங்கி வானத்து நட்சத்திரங்கள், எரிநட்சத்திரங்கள், இலங்கைக்கு மேலால போகும் செயற்கைக் கோள் எல்லாம் காட்டுவார். பிள்ளைக்கு நோகாமல் வளர்த்தெடுக்க வேணும் எண்டு நினைச்ச அம்மாவுக்கும், அப்பாவுக்கும் தடுக்க ஏலாது. ஏனெண்டால் மாமா அவையை விட வயசு கூடினவர். அம்மா அவரை அண்ணா எண்டுதான் கூப்பிடுவா. அவரே கூரையில ஏத்தினா என்ன செய்யிறது? அப்பா அப்ப திருகோணமலையிலை வேலைசெயது கொண்டிருந்தார். சுனி ஞாயிறு மட்டும் தான் வீட்டுக்கு வருவார்.

From up on the roof, he showed us insects, birds, stars, asteroids, and even a satellite that floated above Sri Lanka. Our parents who wanted to raise us without having us do any physical activity could not object as Mama was older than them and they couldn’t defy him. Plus, Amma called him Anna! Now if such a respectable adult himself gets children to go up on the roof, what could my mother do? Appa was working in Trincomalee at that time. He only came home for the weekends.

பட்மின்ரனுடன் கலைத்துவமான நிறைய வேறு விடயங்களிலும் மாமா ஆர்வமுள்ளவர். நன்றாகக் கைவேலைகள் செய்வார். அவற்றைப் பார்த்ததும் எனக்கு வாற உற்சாகத்தைப் பார்த்து என்னைக் கிட்டத்தட்ட கைவேலைகளுக்கான தன்னுடைய சி’;யப்பிள்ளையாகவே வைத்திருந்தார் (பட்மின்ரனில நான் வீக்) அவர் தான் முதலில் மக்கரத்தை எனக்கு அறிமுகப்படுத்தியது. பிறகு பலகையில் ஆணிகள் அடித்து வர்ண நூல்களால் பின்னி செய்யும் அலங்காரமும் சொல்லித் தந்தார். நான் செய்த ஒரு வண்ணாத்துப்பு+ச்சி அலங்காரம் கனநாள் எங்கட வீட்டில இருந்தது. இப்படி நூல் கொண்டு பின்னிவரும் கோடுகள் எனக்குப் பிடித்தமானதாக இருந்ததால் இப்பவரைக்கும் அந்த முறைமையை ஒத்த ஆக்கங்களை செய்கிறேன்.

“pi-sigma-delta”, 1987-88

Apart from badminton, Mama was also interested in many artistic things. He was very good at crafts. I would get so excited to see his crafts that he adopted me as his main pupil in handicrafts (I wasn’t that good at badminton). He introduced Macrame to me. He also introduced me to another handicraft where you put nails in a plank and wrap coloured threads around it to make a decorative object. It’s called string art. A butterfly I made that way was in my house for a long time. The patterns in string art inspired many other artistic creations in the years to come.

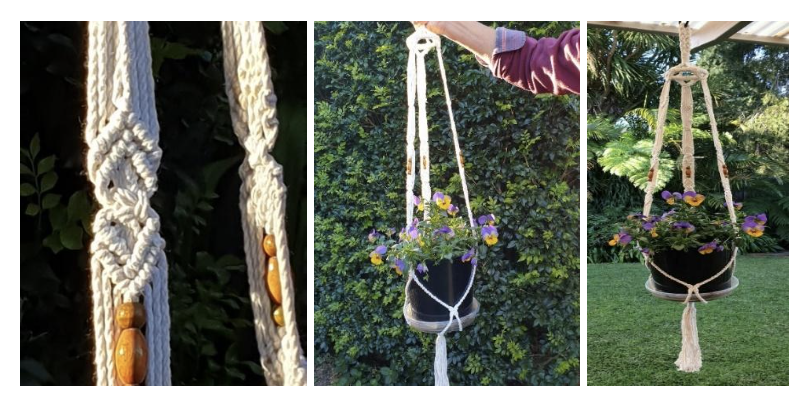

மக்கரம் பின்னுறதை அவருடைய உறவினரான உமையாள் அன்ரி வீட்டில பார்த்தாராம்… அவவோh அவவுடைய அம்மாவோ இதை செய்திருப்பார்கள் போல… அதைப்பார்த்துக் கொண்டிருந்து விட்டு அதே போல நூலும் வளையங்களும், மணிகளும் வாங்கி வந்து தானும் ஒரு ‘மக்கரம்’ பின்னினார். அது வெள்ளை நூலில் பின்னி, சிவப்பு மஞ்சள் மரமணிகள் கோர்க்கப்பட்டு இருந்தது. ஒரு பிளாஸ்ரிக் சட்டியில் பு+வைத்து மக்கரத்தினுள் வைத்துத் தொங்க விட்டிருந்தார். முதலாவதாக எனக்குத்தான் காட்டினார். அதைப்பார்த்து நான் காட்டின உற்சாகத்தில, அடுத்த மக்கரம் பின்னும் போது எனக்கும் காட்டித்தந்தார். பிறகு எனக்கு மெல்லிய பிங்கலர் நூலும் சின்ன மணிகளும் வாங்கி வந்து தந்தார்.

He had seen Macrame at his Umaiyal Aunty’s house. She or her mother had made one. He then bought the threads and beads needed for it. He made a Macrame piece with red and yellow wooden beads smiling on thick white thread. There was a plant in a plastic pot; he had put the pot in the Macrame and hung it. He showed it to me first, before anyone else! I was so excited that the next time he bought things to make a Macrame piece, he showed me how to do it. He bought me thin pink thread and small beads.

எனக்கு கைவேலை செய்யிற, படம் கீறுகிற அவா வந்தால் நித்திரை வராது – படிக்கிற மேசை, படுக்கிற கட்டில் எல்லாம் கைவேலைப் பொருட்களும் பேப்பர், கத்திரிக்கோல் எண்டும் நிரம்பிக் கிடக்கும். அம்மாவும் ஒண்டும் சொல்லுவதில்லை. முக்கியமாக படி, படி எண்டு கரைச்சல் குடுக்கிறதில்லை. வீட்டில் படிக்கும் பழக்கமும் எனக்கு இருந்ததில்லை. கதைப்புத்தகங்கள் மட்டும் வாசிப்பன். வகுப்பில் 5ம் பிள்ளைக்குள் வருவன் – ஒருநாளும் முதலாம் பிள்ளையாக வந்ததில்லை. அது மஞ்சுவின் இடம். இப்பவுள்ள கன பெற்றோர் மாதிரி முதலாம் பிள்ளையாக வந்தேதான் தீர வேணும் எண்ட அழுத்தம் எனக்குத் தரப்பட்டதும் இல்லை.

Once I get into making crafts or drawing, I can’t sleep. My bed, my table, will all be covered in craft things–paper, scissors, etc. Amma didn’t say anything about this. Most importantly, she didn’t keep insisting I study all the time. I didn’t study much at home, anyway. I mostly read story books at home. I would always be among the first five in my class. I was never the first. That was Manju’s place. The pressure we see parents putting on their children today to be the first in class, is not something I faced.

அண்டைக்கு இரவும் நான் இரவிரவாக கட்டிலில இருந்து அந்த மக்கரத்தைப் பின்னி முடிச்சிட்டுத்தான் படுத்தன். எங்களுடைய வீடு அனெக்ஸ் எண்டபடியால் எங்களது படுக்கும் அறைக்கும் பிரதான வீட்டின் ஹோலுக்கும் பொதுவான ஒரு ஜன்னல் இருந்தது. அதை எங்கடை பக்கத்தால தான் திறக்கலாம். காலையிலை அதைத் திறந்து பெரியம்மாவுக்கும், மாமாவுக்கும் காலை வணக்கம் சொல்லுற பழக்கம் இருந்தது. அதோட ஒட்டித் தான் என்னுடைய கட்டில் இருந்தது. அப்ப, விடிய எழும்பின உடனையே ஜன்னல் கதவைத் திறந்தால் மாமாவுக்கு மக்கரம் தெரியிற மாதிரி அதைக் கொளுவி வைத்து விட்டு விடிந்த உடனே மாமாவுக்கு காட்டியுமாச்சு.

I finished making an entire Macrame piece overnight before I went to sleep. There was a common window between the bedroom of our house and the hall of Mama’s house as we lived in the annex. It could only be opened on our side. I had the habit of opening that every morning and saying good morning to Periyamma and Mama. My cot was close to that window. So, I hung the Macrame on the window where Mama could see it first thing in the morning.

அந்த நேரம் அப்பா திருகோணமலையிலை இருந்தபடியால் வாரக்கடைசியில் அவர் வரும் போதுதான் வீட்டுப் பொருட்கள் வாங்குவார்கள். இடையில் அநேகமாக ஒவ்வொரு நாளும் எங்களைப் பார்க்க வரும் அம்மாவின் தம்பி கோபால் மாமாவும், பெரியம்மாவின் மகன் ராதாண்ணாவும் வேறு உறவினர்களும் ஏதாவது தேவைப்பட்டால் வாங்கி வந்து குடுப்பார்கள். நானும் சைக்கிளிலை சந்திக்கடைகளுக்குப் போய் சாமான்கள் வாங்குவன்.

As Appa was in Trincomalee at that time, they only bought household provisions at the end of the week when he came home. In between, relatives who came to see us–my mother’s brother Gopal Mama, my periyamma’s son Ratha Anna, and others–bought the things we needed. I also went on my bicycle to buy things.

ஆனால் மாதத்துக்குரிய முக்கியமான பொருட்களை மாதம் ஒன்றோ இரண்டோ தடவைகள் ஒட்டுமொத்தமாக வாங்குவது யாழ்ப்பாண கோப்பில் தான். இந்த கோப் – யாழ்ப்பாண கூட்டுறவுச்சங்கத்தின் பெரிய கடை பெரியாஸ்பத்திரிக்கு முன்னால இருந்தது. அதில் பலரும் சிறுசிறு பங்குதாரர்களாக இருந்ததாகவும் அப்பாவும் சில பங்குகள் வைத்திருந்ததாகவும் கதைத்த ஞாபகம். அங்கு மளிகைப் பொருட்களுடன் வீட்டுக்குத் தேவையான பாத்திரங்கள், கோப்பைகள் போன்ற பாவனைப் பொருட்களும் இருந்தன.

Now, monthly provisions were bought once or twice a month at the Jaffna Co-Op. This shop was the main storefront of the Jaffna Cooperative Society. It was in front of the Big Hospital. Many people were members of the Co-Op. I remember hearing that my father was a member of the Co-Op, too. Apart from provisions, the shop also sold dishes, cups, etc., for household use.

எங்களுக்கு அங்கு ஒரு கடன் கொப்பி இருந்தது. அம்மா எழுதித்தரும் பட்டியலைக் கொடுத்தால் அவர்கள் அவற்றைச்சரைகளிலும் பொதிகளிலும் கட்டி பெட்டியில் அடுக்கி, கொப்பியிலும் கணக்கு எழுதிக் கொடுப்பார்கள். சம்பளம் எடுத்தபின்னர் அப்பா மொத்தமாகக் கட்டுவார். அப்பாவுடன் நானும் தம்பியும் அங்கு போயிருக்கிறம். நீண்ட நாள் தொடர்புள்ளவர்கள் எண்டதால் அனைவரும் அன்பாகப் பழகுவார்கள். எங்களுக்கு இனிப்புக்களும் தருவார்கள். அப்பா திருகோணமலையில் இருந்த நேரம் சிலவேளைகளில் கடனுக்கு சாமான்கள் வாங்க வேண்டியிருந்தால் அம்மா என்னிடம் பட்டியலைத் தந்து அனுப்புவா. நான் சைக்கிளில கோப்பிற்குப் போய் அங்கிருக்கும் அண்ணாக்களிடம் துண்டைக் கொடுத்தால் அவர்கள் எல்லாவற்றையும் கட்டிப் பெட்டியில வைச்சு, பெட்டியை எனது சைக்கிளின் கரியரில் வைத்துக் கட்டி விடுவார்கள். வீட்டுக்கு வந்தால் அம்மா அவற்றை அவிட்டு எடுப்பா. கோப்பிலை அண்ணாக்கள் சாமான்களை கட்டுகிற நேரம் நான் கோப்புக்குள் இருக்கிற பொருட்களை ஒரு சுற்று சுற்றிப் பார்த்துவிட்டு வருவன். முக்கியமாகப் பீங்கான் கண்ணாடிப் பொருட்கள் இருக்கும் இடம் நல்ல விருப்பம். குறிப்பாக வர்ணம் தெறிக்கும் பளிங்குக்கண்ணாடிப் பொருட்களில் சரியான ஆசை… இன்றுவரை…

We had an account notebook at the Co-Op. My mother would send the list. I would give that list to the shop people. They would pack and arrange all the things in a box and write up the bill in our notebook. Appa would pay the bill all together after he got his salary every month. My brother and I had been going there with Appa since we were small, so everybody would always be sweet and give us treats to eat. When Appa was in Trincomalee, we sometimes bought things on credit. Amma would hand me the list and I would go on my bike and hand the list to the annas in the shop. They would put all the things in a box and tie the box to my carrier. At home, Amma would untie the box and take the things. While the annas packed and tied up the things to my bicycle, I would go around the Co-Op and gaze at all the other things. I was most interested in the ceramic and glass items shelf! I loved the vibrant colours on the glass things. Still love them.

அந்தநேரம் யாழ்ப்பாணத்திலை அழகான குளிர்பானம் குடிக்கும் சின்னச்சின்ன வர்ணமூட்டப்பட்ட கண்ணாடிக்குவளைகள் (கிளாசுகள்) அறிமுகமாகியிருந்தன. கோப்பிலும் அடுக்கப்பட்டிருக்கும் அந்த கிளாசுகளில எனக்கொரு கண். ஆனால், வீட்டிலிருக்கும் தேவையான பொருட்களுக்கு மேலதிகமாக ஏதாவது கேட்டால் அம்மா ஏசுவா… பார்த்துப் பார்த்து வைச்சிருந்தன்…

During that time, small, colourful glasses for drinking cold drinks were introduced in Jaffna. There was something that always pulled me toward them, and so when I eyed those glasses on the shelves in the Co-Op, I just wanted to possess them. But this was not simple. For if we asked for things beyond what we needed at home, Amma would get upset. So, I just took them in. Quietly.

இப்ப நான் மாமா வாங்கித்தந்த மெல்லிய நூலில மக்கரம் செய்திட்டன். அம்மாவுக்கும் நம்பிக்கை வந்திட்டுது. அவ எனக்கு நல்ல தடித்த நூலும், வளையமும், மர மணிகளும் வாங்கக் காசு தந்தா. முதல்தரம் மாமா தான் வாங்கித் தந்தார். பிறகு நானே போய் வாங்குவன். நூல் அநேகமாக மீன் வலை சாரந்த பொருட்கள் விற்கும் கடைகளில கிடைக்கும். மணிகள் அரஸ்கோ கொம்பனி என்று நினைக்கிறன் – அவையிட ஒரு கடையில கிடைக்கும். அங்கு மரத்தால செய்த வேற நிறைய விளையாட்டுப் பொருட்களும் இருக்கும். அதுக்குள்ள மரத்தால செய்த சின்னத் தேர் ஒன்று எனக்கு மிகவும் பிடித்தது…

After I made the Macrame out of the thread Mama gave me, Amma was convinced that I could do this craft. So, Amma gave me money to buy thick thread, a hook, and wooden beads. The first time, Mama helped me buy the things at the shops. After that, I went by myself. The thread was mostly available in shops where you buy fish nets and related things. The beads had to be bought from a shop which was called Arasco Company, I think. They had many toys made of wood. There was a small chariot made of wood in that shop. I really liked it.

நான் வெள்ளை நூலில் செய்த முதலாவது மக்கரத்தை ஹோலுக்குள் இருந்த ஒரு வளைவிலை கொளுவியிருந்தன். பின்னேரம் வீட்டுக்கு வந்த ராதா அண்ணா அதைத் தனக்குத் தரச் சொல்லி உடனையே காசு தந்து வாங்கீட்டார். இன்னும் இரண்டு செய்து தரச் சொல்லி அதுக்கும் காசு தந்திட்டார். பெரியம்மாவிடை கடைசி மகள் ஜெயந்தி அக்கா கல்யாணம் செய்து அவுஸ்திரேலியாவுக்கு போகும் போதும் ஒன்று கொடுத்து விட்ட ஞாபகம்… அவ இப்பவும் அதைக் கவனமாக வைச்சிருக்கிறா. அதுக்குப் பிறகு கொஞ்சநாள் வேற வேற நண்பர்களும் உறவினர்களும் என்னைக் கொண்டு மக்கரம் செய்விச்சு தங்கடை வீடுகளிலை கொளுவிச்சினம். இதிலை எனக்கு சின்னதாக ஒரு சேமிப்பும் கிடைச்சுது.

I had hung the first Macrame I made from white thread in the hall. Ratha Anna, who came over in the evening, immediately took that one and gave me money to make two more. I remember giving one to the last daughter of my periyamma, Jayanthi Akka, before she got married and went to Australia. She has kept it carefully to this day. After that many more relatives got me to make Macrame and hung it in their houses. I earned a small amount of money from this.

அதுக்குப் பிறகு கோப்புக்கு சாமான் வாங்க அம்மா அனுப்பின நேரம் சேர்த்து வைச்ச அந்தக்காசையும் கொண்டு போனன். அங்க பார்த்து வைத்திருந்த பச்சைக் கண்ணாடி கிளாஸ் ஆறு கொண்ட செட் ஒன்றை மெள்ள வாங்கிக் கொண்டு வந்திட்டன். சைக்கிளிட முன்கூடையில கவனமா வைச்சுக் கொண்டு வந்தன். அம்மா ஒண்டும் சொல்லேல்லை.

The next time Amma sent me to the Co-Op to buy things, I took the money that I had saved up. I bought a set of six green glasses that I had been dreaming of possessing. I put those precious things in my bicycle’s basket and rode home slowly and carefully as if my life depended on them. Amma didn’t say a word.

அதுக்குப் பிறகு 83ம் ஆண்டில வீடு மாறிக் கைலாச பிள்ளையார் கோவிலடிக்கு வந்திட்டம். சண்டையும் தொடங்கீற்றுது. சிலநேரத்திலை அந்த வீடே ஒரு அகதிமுகாம் மாதிரி இருக்கும்… யாழ்ப்பாணத்துக்குள்ளயே வேற வேற இடங்களில இருந்து குண்டுகளுக்குப் பயந்து ஓடி வந்த உறவினர்களால வீடு நிரம்பி இருக்கும்;. சிலநேரம் நாங்களும் வீட்டை விட்டு இடம்பெயர்ந்திருப்பம். பிறகு நான் 90இல கம்பஸ் முடிச்சு கொழும்புக்கும் அங்கை இங்கையெண்டும் திரிஞ்சிட்டு 95இல ஜெயசங்கரோட மட்டக்களப்புக்கு வந்திட்டன். அந்த நேரம் ஆமி யாழ்ப்பாணக் குடாநாட்டைப் பிடிக்கிறதுக்காக நகரத் தொடங்கீட்டாங்கள். ஜெயாவுக்கு மட்டக்களப்பு கம்பஸில வேலை கிடைச்சதால நாங்கள் 95ம் ஆண்டு ஆவணியில பெருத்த சண்டைக்குள்ளை யாழ்ப்பாணத்திலையிருந்து வெளிக்கிட்டனாங்கள். அதிலையிருந்து 2 மாசத்துக்குள்ளை யாழ்ப்பாணக் குடாவுக்குள்ளை இருந்த ஏறத்தாழ முழுச்சனமும் இடம்பெயர வேண்டி வந்திட்டுது. என்ர வீட்டுக்காரரும் மந்துவிலிலை சித்திராக்கா வீட்டில போய் இருந்தவை. சித்திரா அக்கா மனோகரன் மச்சானின் மனைவி. அவை உடுவிலில தான் இருந்தவை. பிறகு இடம்பெயர்ந்து அவவிட சீதன வீட்டுக்குப் போய்ட்டினம். அங்கு தான் என்னுடைய வீட்டுகு;காரரும், வேற நிறைய சொந்தக்காரரும் போயிருந்தவை. அம்மா இறந்து, செத்தவீடும் அங்கதான் நடந்தது. நான் அதுக்கும் போக முடியாதளவு யுத்தம். அம்மா 1996 மாசியில இறந்தவ… (இடையில வேறயா எழுதக் கனகதை இருக்குது).

Later, in 1983, we moved to a house near Kailasa Pillaiyar Kovil. The war had begun. Our house was often like a refugee camp. Many relatives, afraid of shelling in different areas of Jaffna, came to our house. The house would be full. Sometimes we, too, were displaced from our own home. Upon finishing my BSc on campus in Jaffna in 1990, I roamed around in Colombo and elsewhere. Finally, in 1995, I came to Batticaloa with Jeyasankar, my husband. At that time, the army was moving in to capture the Jaffna Peninsula. We left Jaffna in the midst of intense fighting as Jeya got a job at the Batticaloa Eastern University in August-September of 1995. Two months later, almost the entire population of the Jaffna Peninsula were forced to leave their homes. My family members were also displaced and were at Chitra Akka’s house in Mandhuvil. Chitra Akka is Manoharan Machchan’s wife. They were in Uduvil earlier but were displaced and moved to their dowry house. My father, mother, brother, and many other relatives were there. Amma’s death and her funeral were in that house, too. I couldn’t go to the funeral. That’s how bad the war was. Amma died in February 1996. There are many more stories from this period…

பிறகு 2002இல தான் எனக்கு யாழ்ப்பாணம் போகக் கிடைத்தது. அப்ப அப்பாவும் தம்பியும் கைலாச பிள்ளையார் கோவிலடி வீட்டில இருந்திச்சினம். நான் விட்டுட்டு வந்த என்னுடைய ஆக்க வேலைகள் ஓவியங்கள், உடுப்புக்கள் எண்டு நிறைய சாமான்கள் அழிந்தும் தொலைந்தும் போயிருக்க அம்மாவின் சமையலறைக்குள்ள சுவரோட கட்டியிருந்த அலுமாரியிட அடித்தட்டு மூலையிலை இந்தக் கண்ணாடிக்கிளாசுகள் – அவை வந்த பெட்டியோடையே பத்திரமாக இருந்திச்சினம். பிள்ளையிடை முதல் உழைப்பிலை வாங்கின பொருளை அம்மா கவனமாக பாவிக்காமல் வைச்சிருந்திருக்கிறா.

After that, I only went to Jaffna in 2002.

Appa and my brother were in the house near Kailasa Pillaiyar Kovil. Many of the things I had left behind were destroyed in the war–my art works, my clothes, so many big and small things that made me. But there in Amma’s kitchen, in the corner of the bottom-most shelf of a cupboard that was built into the wall, were the green glasses. Safe in the box I had bought them in. My mother had left them untouched. She had saved them as they were bought from her child’s first income.

அதுக்குப்பிறகு அந்த கிளாஸெல்லாம் என்னோட மட்டக்களப்புக்கு வந்து மூண்டு நாலுதரம் இடம் மாறேக்கை பயணிச்சு இப்பவும் 5 பேர் பத்திரமாக இருக்கினம்.

After that, those glasses returned with me to Batticaloa. They have gone with me as we changed homes three or four times. Even now, five of them are with me.

கிளாஸ் வாங்கின கோப் இருந்த இடத்திலை இப்ப கார்கில்ஸ் சதுக்கம் இருக்குது.

Today, the place where the Co-Op was is called Cargills Square, named after a large corporate entity that has supermarkets all over the country.

Reflections…

The first time I heard this story, I was already mesmerized by the detail with which Vasuki remembers little Vasuki’s excitement, passion, and spirit. For any person, this is a precious gift. For Vasuki, who, since a very young age has lived through war, it is that much more valuable. And then, of course, as the story progresses, the places where the glasses enter her life are simply beautiful. The charm of her inhabiting public space as a young child, bicycling through a Jaffna that is to be destroyed to ashes only a few years after, is hopeful. I found myself thankful for these years in her life. I am thankful that she has these memories. I am thankful that we all have these stories.

She got the green glasses when she was fifteen or sixteen, from money she saved from making Macrame art which her relatives bought from her. She is parted from the glasses for almost two decades. They re-enter her life after her mother has passed, but the glasses remain safely in her kitchen cabinet. I have broken down every time I have heard or read this. The sheer determination of her mother who protected half a dozen easily breakable glasses through years of shelling–even as her home, her town, and her people are destroyed all around her–evokes a sense of hope in the human spirit. A spirit that defies language.

Living with this story for many months now has brought home emotive insights that could possibly help us reimagine the ways in which we listen to stories of war. In building reflections with Vasuki, she and I have consciously centered on her life and art. A small hope guides this conscious choice: that such a centering, which is often not considered an essential part of war narratives, will provide new lenses through which we can pay heed and bear witness to these histories. Thankfully, this approach is not rare for the history of the war in Sri Lanka anymore. Many projects are already structured around telling the story of the war through individual stories, objects, and art. Archive of the memory, Memory Map Sri Lanka, Historical Dialogue, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, We Are From Here and Right to the City -SL are just a few examples of such works.

The things I want to add to this are my reflections on the tone, the pace, the pauses, the rushes, and the silences in how this story was told to me and how Vasuki has put it down in written form in Tamil. These tell us a lot about all that we must mull over to tell stories of human brutality while putting people, with all their complexity and nuance, at the center.

The story began in its spoken form and also in the written form above with a description, in a slow pace and in detail. The descriptions are that of the place, people, and feelings of the times that are of play, joy, and passionate learning–in this case learning the craft of Macrame. The reader/listener can imagine the dusty lanes, the smells, the different levels (literal and emotional) from which Vasuki, her fellow children, and the adults around them viewed the world in the everyday. We can sense the smooth efficiency and the predictability of a Sri Lankan town in the late 1970s and early 80s. A time without as much excess as there is now even as enough new things were coming in to incite excitement and longing. We get to know so many characters in this part of the story. I can imagine the smallest of characters who play a big role, like Radha Anna who bought the very first Macrame Vasuki made and gave her money to make two more. I can imagine him–a slightly older man, proud of his cousin sister for having made a beautiful thing which, in turn, he wants to take with him to beautify his own home. The simple joys of life. I can imagine what a large figure Mama was in the lives of these children. Mama from all accounts seems to have been genuinely invested in the children, their physical health (through badminton), and their creativity. It only makes sense, as he is a teacher and is a son of a teacher. In a place that is at the verge of an impending war, with tensions that are already beginning to build up, Vasuki is describing an adult figure who helped the children to climb up on to roofs to gaze at the open sky. We can hear and feel in Vasuki’s description how much this expanded the horizons of her childhood world..

Vasuki’s excitement at showing him her first Macrame by hanging it on the shared window between their two houses always makes me smile. We now know the role that making art, any art, has played in making Vasuki who she is today. This series exists because of the profound influence of Vasuki’s journey with art and life, on herself and on the myriad histories of people, places, and movements. Many adults nurtured Vasuki even as she nourished her love of art-making. Her mother, who wasn’t cross with her for not doing school work or for spreading her art materials all over the house. Her mama who taught her the craft and encouraged her passion for it. These are only a few of the many things that played a seemingly small but essential part in Vasuki’s continuing nourishment of her passion for art.

In the run up to the green glasses entering Vasuki’s life, Radha Anna’s simple joy in Vasuki’s creation and the encouragement he provides brings a sense of non-rupture in relationships, familial attachments, and people’s investment in beauty in their home spaces. None of these can be taken for granted knowing what we know now about the relationships, families, and home spaces that got destroyed in just a few years after Vasuki made her first Macrame. This non-rupture of social spaces and relationships also becomes palpable in the sense of safety that Vasuki feels in her place of living. This sense of safety comes through when she describes how the annas at the Co-op would carefully tie up and arrange all the provisions on her mother’s list into a box and tie the box safely to her bicycle. To be un-tied by her mother at home. All Vasuki had to do was to cycle through familiar roads and faces and get herself and the box home. Today, there aren’t many places in the world where we could send the girls in our lives out to a shop and expect such communal care. That sense of familiarity and the safety it brings is a thing of the past in the midst of the anonymity that capitalism has bred.

In Jaffna, these streets, this Co-Op, and this familiarity are among the sacred things that were obliterated by the war. It isn’t as if that city, its streets, and its people didn’t live in the midst of stringent caste and class hierarchies. It isn’t as if patriarchy didn’t form the premise for all human interaction. Yet, the safety of everyday life in a non-war context, even when marked by multiple structures of oppression, does make space for stability, especially for younger minds and bodies. This, in turn, could form the foundation to imagine freedom from those very structures of oppression. Perhaps it played such a role for Vasuki. Emotive realities of how everyday life is experienced are profoundly influenced, and yet not subsumed, by structures of oppression. It is all just much more complicated than that. This is why we all have such complex, often seemingly contradictory and sometimes vexed relationships with places and people who may be deemed ‘our own.’

This same everyday life, when destroyed by war, however, creates a sense of profound rupture in a person. This rupture is all around us here in Sri Lanka. A wound, a scar, an all consuming hole whose beginnings, ends, and middles are sometimes hard to identify, realize, or acknowledge.

Just before this rupture occurs for Vasuki, the green glasses enter her life. Via her familiar Co-Op, in her hometown, through craft she made as a result of a significant relationship with a well-meaning and creative adult.

Vasuki and her amma never quite spoke about the glasses in words.

Until this point, there is detail, nuance, and a slow pace to the story. After this, the story suddenly moves into a rushed pace. In the oral telling, as in the written version, there were heavy sentences full of a thousand more stories untold. Filled with disturbing images of every person around Vasuki being consumed by fear and the sheer grit needed for survival. From 1983 to 1996, Vasuki rushes through the main highlights and moves past them with a starkly different pace than in the earlier section. I experience this section as her trying to sprint on a rugged road full of rocks, with a very heavy bag that is pulling her down. In this image, I see Vasuki thudding to the ground in 1996. Her mother died and she is unable to return to Jaffna because of the war. This story of not being able to go to the funerals of parents, husbands, wives, siblings, close friends, lovers, and so many others we hold dear is one of the most heartbreaking stories of the war. It is one thing to not be able to live in peace, it is quite another to not be able to pay our respects to the dead. In the story (or in me, I am not sure) the space between the two sentences that follow one another–

‘Amma died in 1996’

and

‘After that, I only went to Jaffna in 2002’…is extremely heavy. It feels like the bottom of a well or the weight of a large rock crushing from above or both. Perhaps it is that weight–of those sentences, those years, and those breaths the storyteller and listener took–that gets released in tears every time I read or hear about that moment when the green glasses re-enter Vasuki’s life.

That inbuilt cupboard in her amma’s kitchen that helped her protect the green glasses through unspeakable violence becomes a holder of the circularity of grief, and also hope.

The circularity in the presence and absence of the green glasses in Vasuki’s life is a symbol of how we grieve and hope through war. It is the union of grief and hope, like the threads in a Macrame piece: deeply interlaced re-tellings of the war that defy dichotomies and that enable us to see some of the lost pieces of people, places, and histories.

As Vasuki and I continued to live with this story, Vasuki tried to find out if Jayanthi Akka who got married and went to Australia still had the Macrame she had gifted her. She still did. Here is a picture of that piece hanging in a garden, in far away Australia.

And so, the cycle of grief and hope, interlaced and making a beautiful pattern together, breathes across times, places, people, oceans, and hearts.

Article by: